Happy Spring! The best season! With the warming temperatures a bright feeling is upon me, as I hope is true for many of you too, though ever alongside the despair of yet another American tragedy. More on this next week, when I return to normal programming.

For now I leave you with the second part of The Sisterhood of Jewish Cooking, with heartfelt thanks for the various ways many of you were in touch last week. Many of you shared fond food memories from your own grandmas, which were a true joy to read. And a few of you chimed in with your own mid-century family recipes, like Swedish meatballs made with ground beef, a jar of chili sauce, and a jar of grape jelly; and the “24 hour salad”: a base of spinach layered with a mix of sour cream, mayo, and green onion, a layer of hardboiled eggs and peas, repeat those layers x2, and finish with a top layer of mayo, sour cream, eggs, and bacon sprinkles. (!!!)

*Lastly, I must issue a correction: In part 1 I say tunafish with dairy is not kosher, but not so! Tuna is not considered meat—any fish with fins and scales isn’t—so the combo is most definitely allowed. (Hello, smoked salmon and cream cheese, herring in cream, etc!)*

I am very fortunate to say that identifying as Jewish has only infrequently made me feel alien. Growing up on the Upper West Side of Manhattan, which they say has as many Jews per capita as Israel, it was more unusual in school not to be Jewish at all. This had the very funny effect of making Jewishness seem boring, ordinary, and undesirable. From what I could tell, being Jewish was terrifying Passover Seders at Aunt Lila’s house, the competitive sporting of Bar/Bat Mitzvah season, a lack of Christmas and Easter, and gefilte fish. So I pushed back. I dropped out of Hebrew school and refused to be Bat Mitzvah’d. We observed the traditions, and continue to, but my knowledge of and interest in them is passing at best. My great sisterhood was the gymnastics team. I celebrated my secularity with everything I had, and with surprising conviction. Then I went to college.

It was week one, an athlete from Orange County. “I heard you were Jewish? Is that true?” He asked. I winced, flabbergasted as to why this fact was being mentioned now, and had been previously by others, without me there. “Because you’re pretty cute for a Jew,” he added, content to pay me a compliment. Then I went to France, certainly the most Anti-Semitic, proudly liberal Western country. The father in my kind host family was a political cartoonist, whose favorite subject seemed to be skewering Jews for all the world’s ills, complete with giant noses, horns, and moneybags. He showed off his work with pride, and I lied about how excited I was to go home for Christmas.

I got the picture. Jewishness is absolutely precious because Anti-Semitism is quite literally as old as time, and ever-pervasive in ways big and small. So I started to care more and learn more and observe more mindfully. I studied Jewish history in Europe in graduate school and wrote my Masters’ thesis on the legend of the Wandering Jew. I am still not religious and never will be, as I disagree with many of the principles of devout Jewish orthodoxy, but I’ve come to understand that the deliberate keeping of tradition is precisely the internal mandate that has ensured our community is not stamped out, by the everyone who has wanted to.

Nevertheless, the poetics of assimilation are complicated. Still not all the way content with my heritage, I recently had my DNA analyzed through 23andMe, hoping to discover some exotic ancestry. The results: 99.9% Ashkenazi Jewish, from Eastern Europe. It was admittedly pretty funny, but also troubling. For one thing, this result was not accompanied by precise national or regional origin, which is typical of the findings for other users. More importantly, the abiding debate over Jewishness as religious choice or ethnicity seemed tossed out the window. It would seem I am Jewish down to every molecule, regardless of my national affiliation or how religious I choose to be. It presented me point blank with the fundamental tension I, and all assimilating Jews, have wrestled with: the perceived safety of an internal sense of assimilation, against the stigma and danger of being seen by others only as a Jew.

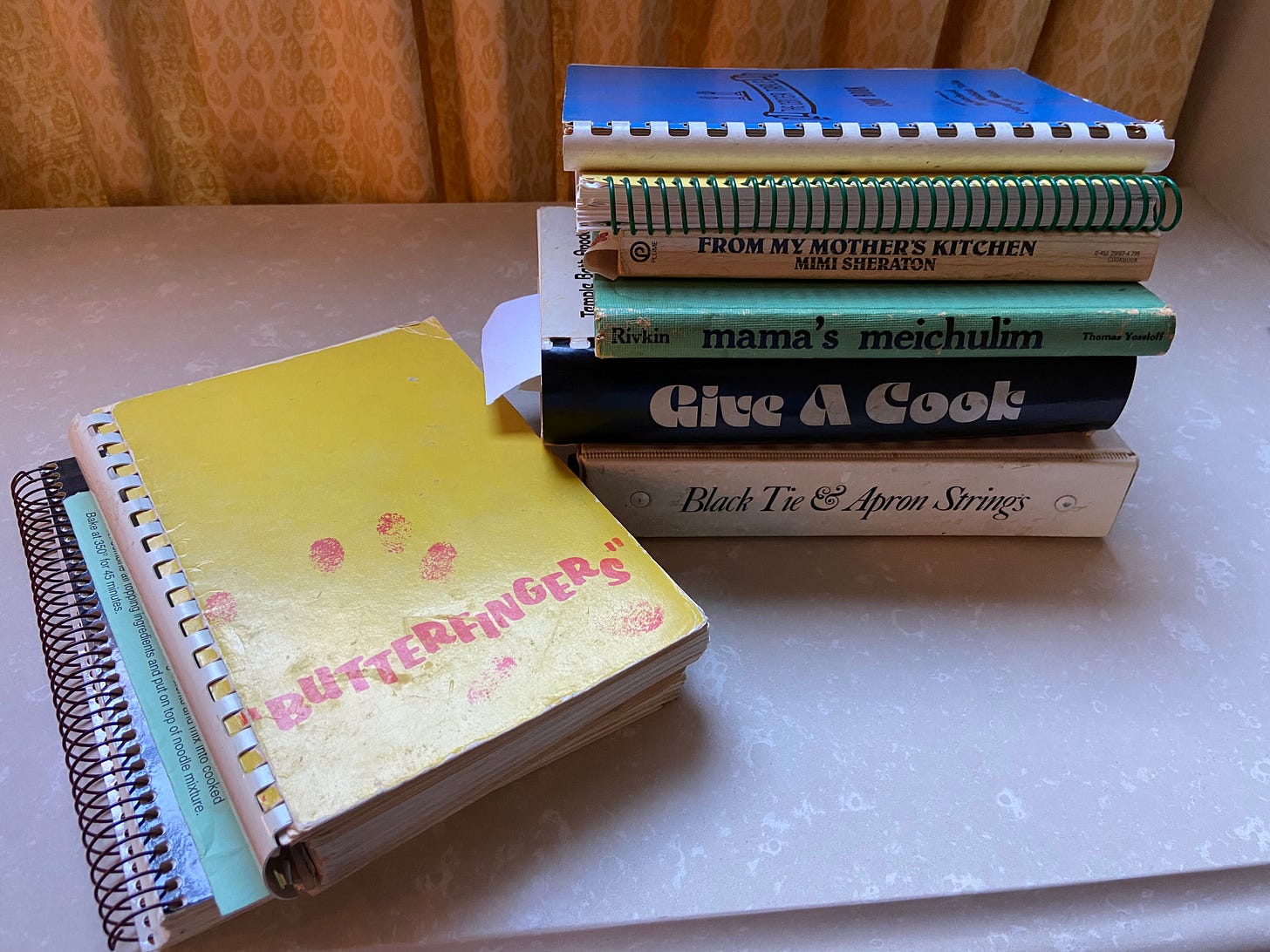

For any endangered minority, it is an enormous privilege of safety to look and to be anonymous in your body. My appearance is pretty ambiguous, and I very much enjoy this privilege. So when I was first told I looked Jewish, I didn’t totally understand why I found it—and find it, when it happens—so offensive. Part of it is, perhaps, an internalized anti-Semitic ideal of beauty, which is insidious. Even worse is the feeling of exposure. My Jewishness is mine, and mine to telegraph if I want to. Someone else’s taking notice—however innocently intentioned—is freighted with all the terrible danger and history of being othered; of being the outsider. This is part of why Jewish people stick together in great communities all over the world, so we don’t feel unduly visible. This is also why these community cookbooks are such important affirmations—a snapshot in time of perfectly imperfect Jewishness, the old traditions intermingling with the new.

I find myself longing, too, for the would-be cookbook of my great-great Aunts Molly, Dora, Mae, Sophie, and Sylvia. Though Americans, they were really still immigrants; their traditions and recipes were deeply local, passed down by necessity and osmosis, and in a combination of English and Yiddish. This was the food my people survived on through brutal winters and pogroms. Pre-war, they didn’t have the processed food, mixmasters, or shortcuts. Their recipes would’ve been all grit, authenticity, and regional specificity—not the blandly denuded, consumerist-assimilationist version that succeeded them, which is part of what I found so uninspiring growing up. I’m disappointed in myself for feeling that way. It is precisely from my place of secular, assimilated privilege that I can be flippant about the very markers of their successful, and absolutely necessary, American integration.

In the end, inside these cookbooks is a truth that never changed—cooking was a world entirely devoid of men. The fluency and comfort inside these spaces was a province foreign to husbands, not welcome or able to enter. While I’m sure not enough men expressed adequate appreciation for this ceaseless labor, both at home and for the community, I surmise that in the sisterhood there was immense power—in its friendship and commiseration. I love to imagine Cookie as a young mother: a total superstar, full of energy, the keeper and promulgator of traditions big and small, mistress of her universe, firmly rooted in and supported by a community of women she adored, and who adored her. I haven’t always understood what made that so special, but I’m starting to.

For what it’s worth, Cookie didn’t use the sisterhood cookbooks very much while she raised her family. She didn’t really need them for inspiration or instruction, and she wasn’t the type to want to take the shortcuts they offered. A lifelong cooking overachiever, she’s proud of this fact. But just as it was with her big sisters, her life-saving aunts, and her family of female friends, you get the sense she just felt better knowing they were there.

Thank you for reading The Culture Diet <3 If you’re new here, a most warm welcome. I’m a curator and writer based in NYC, having spent a decade working in the art world. What you’ll get here is interdisciplinary cultural commentary, personal essays, thoughts on art, things to consume, and whatever else inspires, outrages, and delights me. If you’re enjoying it, please subscribe and tell your friends!